by Sarah Weinman

Metta Fuller Victor

The story of crime fiction in America has been largely understood as a male one. Starting with the terrifying tales of Edgar Allan Poe, moving to early “Great Detective” imitations of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, on to the hardboiled tradition created and perfected by Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, expanded to a mass audience by pulp paperback novels, and further refined and honed by the likes of David Goodis, Ross Macdonald, and Elmore Leonard.

Anna Katherine Green

That story, of course, is far from the truth. In fact, women were publishing crime fiction from close to its inception, with Metta Fuller Victor (The Dead Letter) and Anna Katherine Green (The Leavenworth Case) beating Conan Doyle to the detective punch in 1866 and 1878, respectively, and Carolyn Wells publishing her Fleming Stone series soon after. That women were always part of the tradition somehow got sanded over, whether by accident or willful design, even though they were always there, paving their own distinct pathways through the rules and tropes of the genre. They took as much from deductive ratiocination as they did from the Gothic tradition made famous by the Bronte sisters.

What we take to be the earliest of modern American crime fiction grew out of pulp fiction magazines founded in the early 1920s. Something darker and more amorphous emerged in the weedier, seedier corners occupied by the pulps, allowing the brute nihilism of Carroll John Daly, James M. Cain, Paul Cain (no relation), and Dashiell Hammett, among others, to gather serious followings in magazines like Black Mask and Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine. They had seen the worst the world offered during World War I and instead of retreating into rarefied worlds and detecting clubs, they embraced the darkness, the tough, clipped language, the heavy action and doomed endings. They were Edgar Allan Poe’s horror tales gone modern, rewritten in contemporary vernacular.

Dorothy L. Sayers

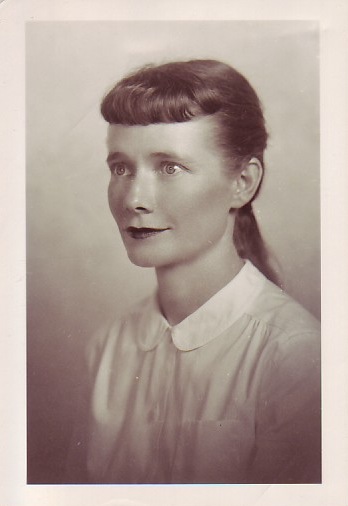

Nedra Tyre

The tension of being trapped in an unhappy marriage, or of an independent life being snatched away, of being a misfit within a community, found fruit—of the poisoned kind—within domestic suspense stories. Domestic suspense is the mirror image of romance fiction; where romance is about conflict resolving into a happy ending, domestic suspense is about a happy beginning (of marriage, children, or independence) splintering into chaos. With the post-war economy on the upswing and new technology, like inexpensive cars and kitchen appliances, freshly available to couples and families, it seemed a simple thing to slip back into traditional roles of wifehood and motherhood, even if those roles were outmoded. Novels of domestic suspense took the fantasy of suburban living and uncovered the bile and dreck subsisting underneath, a clever subversion that also doubled as a mirror to sublimated terror.

By Sarah Weinman, editor of LOA’s Women Crime Writers boxed set

Sarah Weinman is widely recognized as a leading authority on crime fiction. She is the editor of Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Stories from the Trailblazers of Domestic Suspense, which the Los Angeles Review of Books called “simply one of the most significant anthologies of crime fiction, ever.” She is the news editor for Publishers Marketplace, and her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, the National Post, and The Washington Post, among other publications.

Sarah Weinman is widely recognized as a leading authority on crime fiction. She is the editor of Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Stories from the Trailblazers of Domestic Suspense, which the Los Angeles Review of Books called “simply one of the most significant anthologies of crime fiction, ever.” She is the news editor for Publishers Marketplace, and her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, the National Post, and The Washington Post, among other publications.